Amy Winehouse may have considered herself less of a star and more of a smoldering candle casting a dim glow over the booze-soaked patrons in a smoky basement club, adding to the romantic danger of it all.

But not many flames burned as brightly as hers did before the demons she commemorated in song extinguished it when she was only 27 years old.

Winehouse had a lived-in voice that dripped with experience and belied her youth, as if she was born to warble torch songs; a musicality that defied her era; and a seemingly bottomless well of despair from which she conjured her raw, self-deprecating lyrics over the course of two albums released during her lifetime.

The English artist would have turned 36 this year, and both her music and her impact on fellow artists endures, as does her parents’ work in her name to help at-risk youth in London through the Amy Winehouse Foundation.

“The songs I got signed on were the songs that I wrote completely on my own, and if it wasn’t for her, that wouldn’t have happened,” Adele said while performing in Boston on Winehouse’s birthday three years ago. “And so I owe 90 percent of my career to her.”

“The methodology behind what I’ve done is that, when they wanted me to be sexy, or they wanted me to be pop, I always f–kin’ put some absurd spin on it that made me feel like I was still in control,” Lady Gaga says in her 2017 documentary Gaga: Five Foot Two. “So you know what? If I’m gonna be sexy on the VMAs, and sing about the paparazzi, I’m going to do it while I’m bleeding to death and reminding you of what fame did to Marilyn Monroe, the original Norma Jean, and what it did to Anna Nicole Smith, and what it did to….” She paused. “Yeah. You know who.”

About a week after Winehouse died in 2011, a “devastated” Gaga said on The View, “I just think the most unfortunate thing about it all is the way that the media spins things, like, ‘Oh, here, we can learn from Amy’s death.’ I don’t feel that Amy needed to learn any lessons. I felt that the lesson was for the world to be kinder to the super-star. Everybody was so hard on her, and everything that I knew about her was she was the most lovely and nice and kind woman.”

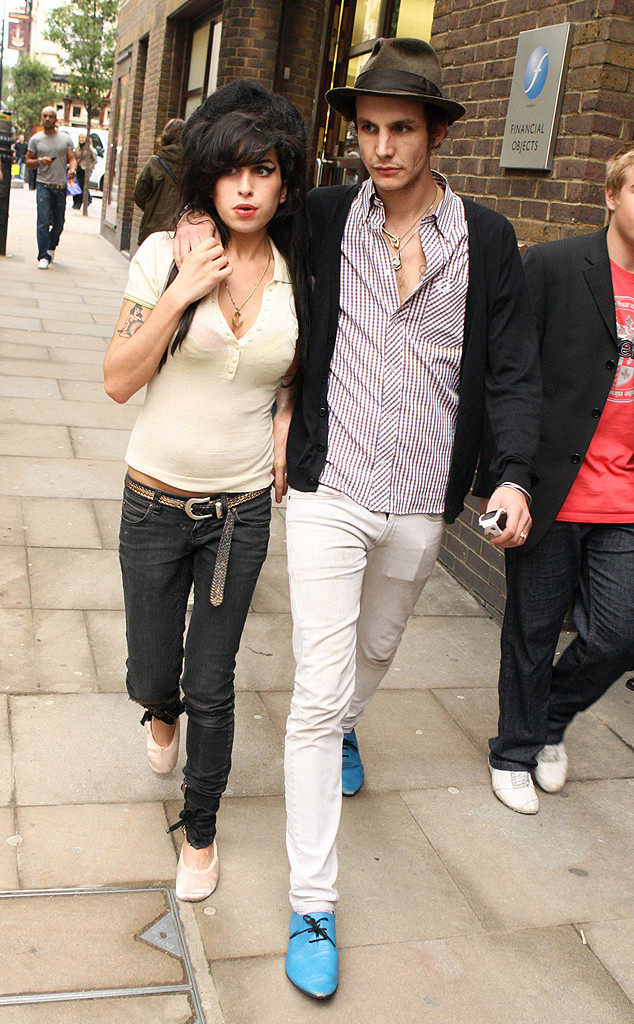

MATT DUNHAM/AP/REX/Shutterstock

Nothing has been revealed over the years to alter that perception. And it was immediately apparent in hindsight that the trajectory of Winehouse’s rise and well-documented fall, and the speed at which her life spun out of control once she was in the public eye, proved to be a vicious cycle. Eventually no one expected any more—or less—from Amy than antics.

In 2008, during a period when Winehouse was holed up in her house and paparazzi were regularly camped outside, her manager at the time, Raye Cosbert, told Britain’s Sunday Times, “She feels deeply uncomfortable in the world of VIP celebrity. It’s unfortunate that you can’t teach somebody how to deal with fame.” And, he added, he knew plenty of male artists who did plenty of drugs, but Winehouse was singled out for heightened scrutiny because she’s “a small-framed Jewish lady from north London.”

The tragedy of it is that all Amy Winehouse ever cared about was making music—she was shocked when someone gave her a break “because,” she told Rolling Stone, “I didn’t think it was special to be able to sing”—and being in love. And yet the increasingly self-destructive spectacle that was her proving she didn’t care what anybody thought of her—making it clear how bored she was with Bono, wandering around outside in her bra—turned into a show in itself.

“The one thing that continues to interest me is human behavior and interaction between two people… even the relationship between me and inside me,” a fresh-faced, 20-year-old Amy mused to APTN in 2004. “I mean, like, ‘Mr. Magic,’ which is about my substance abuse…

“That’s not a good thing to say.”

But she did say it—she belted it, in fact—without remorse. While the immeasurable irony of her music, her biggest hit being about how she didn’t need rehab, is lost on no one, she didn’t intend for her later songs like “Rehab,” “Addicted,” “Back to Black” or “You Know I’m No Good” to be cries for help.

How she was living the rest of her life was a cry for help. The music was salvation.

“I don’t write song because I think it would be a cool idea or because I want to be seen or ’cause I want to be famous,” she told E! News during a swing through Los Angeles in 2007. “I write songs about things I’ve got in my life, that, you know I have trouble with or trouble getting past… Yeah, I had a bad breakup and it was important to me to have something good come out of something bad.”

She didn’t think twice about admitting to her own bad behavior, like cheating, in her music. “I don’t write a song and think, ‘oh, a million people will hear this.’ I write a song because I need to make sense of why I do certain things.”

JEFF PACHOUD/AFP/Getty Images

The title track of 2006’s Back to Black was inspired, for instance, by the slow realization that a toxic relationship wasn’t meant to be and it was time to go back to…whatever normal was.

“When it’s finished you go back to what you know—except I wasn’t working so I couldn’t go and throw myself into work,” she recalled to CNN in 2007. “And when the guy I was seeing went back to his ex-girlfriend I didn’t really –I didn’t have anything to go back to, so I guess I went back to a very black few months, doing silly things as you do when you’re 22 and in love.

“I had about a year and a half off and I was drinking a lot—not anything terrible, I was just trying to forget about the fact that I had finished this relationship. And my management at the time thought I was, well, I wasn’t working so I didn’t see them a lot, they just kind of stepped in and thought they were being the good guys by just stepping in and strong-arming me into a rehabilitation center.

“But,” she shrugged, “just didn’t really need it.”

Winehouse’s jazzy, soulful debut album, Frank, came out in 2003 and was a critical and commercial smash in her native U.K. and was shortlisted for the Mercury Music Prize. She and producer Salaam Remi shared an Ivor Novello Award, which honors composing and songwriting, for the single “Stronger Than Me.” She was nominated for British Female Solo Artist and British Urban Act at the 2004 Brit Awards, and performed at the 2004 Glastonbury Festival.

While her sound continued to combine modern angst with throwback style, she layered on the ’60s influences in her 2006 follow-up, Back to Black, which was buoyed by the mega-hit “Rehab” and made her a global sensation (as well as launched a slew of Amy imitators seeking to capitalize on the retro-soul revival).

For her part, Winehouse counted varied artists ranging from Sarah Vaughan and Thelonious Monk to the Beastie Boys and TLC as her inspirations.

Talking about the impact of Carole King‘s Tapestry had on her life, she told APTN, “I would be amazed and joyed if people could have that with my album… [I’m] more me with the music than I am on any TV thing or any radio thing—because it’s me, it’s my music. It’s the only area of my life where I’m fully confident and fully embrace everything, you know what I mean.”

Her ’60s girl group, “Leader of the Pack” style evolved after Frank.

“I love the ’60s thing,” she told CNN in 2007, “because it’s so naïve and innocent and dramatic, that mentality—but I love that boy with dirty hair who rides a motor bike, and even if he doesn’t love me back I still lie in the road for… Very all or nothing, I like that. I like the mentality.”

“It’s been so long since anybody in the pop world has come out and admitted their flaws, because everyone’s trying so hard to project perfection,” Mark Ronson, who produced Back to Black with Salaam Remi, told Rolling Stone in May 2007. “But Amy will say, like, ‘Yeah, I got drunk and fell down. So what?’ She’s not into self-infatuation and she doesn’t chase fame. She’s lucky that she’s that good, because she doesn’t have to.”

But that didn’t stop fame from chasing her.

By the time “Rehab” was ubiquitous and Winehouse was nominated for six Grammy Awards in 2008 (it came out in October 2006, just missing the cut-off for the 2007 Grammys), her success and monstrous talent had long been overshadowed by her unstable behavior.

She infamously couldn’t accept her five Grammys, including Best New Artist and Record and Song of the Year, or perform in person because the U.S. hadn’t approved her visa in time, her application denied at first due to her ongoing, increasingly public (and international) drug troubles—including an arrest for marijuana possession in Norway in October 2007.

Having shrugged it off years prior, Winehouse finally went to rehab in January 2008, a couple weeks before the Grammys, after a video surfaced on The Sun‘s website in which she appeared to be smoking crack.

Dolled up with her exaggerated cat-eye liner and signature beehive, she ended up performing “Rehab”—every word oozing irony—and “You Know I’m No Good” at the Grammys via satellite from a cabaret setting at Riverside Studios in London, singing in front of a small but enthusiastic audience, including her parents, Mitch and Janis Winehouse.

Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images

She later admitted to reporters she had continued to do drugs the entire time she was in treatment.

In accepting her Record of the Year Grammy for “Rehab,” she memorably thanked her parents and “my Blake incarcerated.”

Her “Blake incarcerated” was her husband of less than a year, Blake Fielder-Civil, who was in jail at the time awaiting trial for his role in a 2006 bar fight. Since meeting at a bar in 2005, they had been off and on, with a lengthy off-period inspiring Back to Black.

“I had never felt the way I feel about him about anyone in my life,” Winehouse told Rolling Stone in May 2007 right after they tied the knot in Miami. “It was very cathartic, because I felt terrible about the way we treated each other. I thought we’d never see each other again. He laughs about it now. He’s like, ‘What do you mean, you thought we’d never see each other again? We love each other. We’ve always loved each other.’ But I don’t think it’s funny. I wanted to die.”

It was as if the tattoo of Blake’s name across her chest was there to keep her heart in place.

“We are so in love, we are a team. Blake, Blake, Blake, Blake, Blake, Blake…” she raved to a journalist in June 2008 while missing her locked-up man. She was getting in so much trouble, she insisted, because “my husband’s away, I’m bored, I’m young. I felt like there was nothing to live for. It’s just been a low ebb.”

For all her declarations of love, Fielder Civil brought out the worst in Winehouse, their domestic disputes at times pouring over into the streets and becoming front-page tabloid news. She had already been making her own headlines for fighting, having punched one female fan in the face in 2006 after the woman suggested she shouldn’t marry Blake.

Hedges/Goffphotos.com

“It was a gig—and she was really rude,” Winehouse explained to E! News in 2007. “And I’m not like that—I’m a violent drunk, very insecure as well. I’m very insecure and I’ve got a thing about bad manners.”

Calling her own behavior “disgusting,” she added, “I haven’t done anything like that in months and months and months and months…I just thought she was very rude. I saw sorry straightaway! Disgusting behavior, really,” she again chided herself. “It’s not excusable.”

Catastrophe watch had already begun, spurred on in no small part by her union with Fielder-Civil, a former production assistant with his own substance abuse issues, and by a number of slurred, detached performances, during some of which she forgot her lyrics, if she bothered to show up at all. In December 2007, she was photographed wandering barefoot around the neighborhood near her flat wearing only jeans and a bright-red bra.

“‘Baby? If I’ve got a vice, when would I know to get it in check?'” she asked Blake in front of the Rolling Stone writer. “I’d tell her,” he replied.

AP Photo/Edmond Terakopian

In June 2008 she was hospitalized after a fainting spell and spent 10 days being treated for a chest infection. Mitch Winehouse said his then-24-year-old daughter was experiencing the early stages of emphysema (that was later walked back to being in danger of developing emphysema). She was supposed to sing the theme song for the latest James Bond installment, Quantum of Solace, but that fell through. She ended up in the hospital again in July after suffering a reaction to medication. Another video leaked, this one of her and a friend singing a sing-song tune composed mainly of racial slurs.

When Fielder-Civil got out of jail that November, he promptly went to rehab and told the now-defunct News of the World that he had introduced Winehouse to crack and heroin (snorted, never injected) and was leaving her—for her own good.

“I have to let her go to save her life,” he told the tabloid. “I am not abandoning her. I am doing this out of love.” He also insisted he wasn’t after her money.

At the time, meanwhile, Winehouse was hospitalized again in London having suffered, according to her rep, another bad reaction to medication. She reportedly overdosed on the drug meant to help her kick drugs. Then Fielder-Civil had to go back to jail after failing a drug test.

She got the message though, and in January 2009 she was photographed in the Caribbean frolicking with a hunky aspiring actor. “I love it here and have never felt so happy,” she told News of the World. “In fact, I don’t think I’m ever going home. Especially as I met Josh here. He couldn’t be more different from my husband, which isn’t a bad thing.” She also said about Blake, per DailyMail.com, “Almost every time I slept with him it was like I was dead.”

Fielder-Civil started divorce proceedings, citing adultery as the cause for their split. Their divorce was finalized in July 2009, with documents showing that Winehouse had admitted to committing adultery in April 2008 and they hadn’t lived together since (partly due, of course, to him being “Blake incarcerated”).

“I don’t think Amy realized we were divorced for months,” Fielder-Civil told The Sun in 2015, claiming that her father—who never approved of the match—forged his daughter’s signature on the papers. “The first time we spoke about it was when she wrote a song called ‘Not a Penny,’ about when she was speaking to Mitch after the divorce and she asked how much I had got and he told her, ‘Not a penny.’ She was thrilled because it proved to her that I wasn’t after her cash.”

Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images for NARAS

He knew she didn’t want the divorce, Blake recalled, “but I was so eager to get it over with and prove that I wasn’t after her money, as her family kept saying, so I signed it.”

So things were already pretty terrible in mid-2008, with Winehouse in and out of the hospital, already suffering the consequences of heavy smoking and her erratic behavior.

She gave a strong performance of “Rehab” and “Valerie” in late June at a star-studded concert for Nelson Mandela‘s 90th birthday in Hyde Park. But by July, London’s Sunday Times was inquiring, “Can Amy Winehouse Be Saved?”

Peter Macdiarmid/Getty Images

“Amy changed overnight after she met Blake,” Nick Godwyn, her first manager, told the paper. “She just sounded completely different. Her personality became more distant. And it seemed to me like that was down to the drugs. When I met her she smoked weed but she thought the people who took class-A drugs were stupid. She used to laugh at them.”

At least she still had her innate talent. The hope that the magic could be recaptured and she would get clean once and for all before it was too late kept the Amy Winehouse machine humming. But on the other end of the spectrum, a world that had watched Britney Spears shave her own head and Lindsay Lohan squander her early talent in a haze of antics that rendered her uninsurable also waited for what felt like the inevitable. And enough music icons before her, from Edith Piaf and Billie Holiday to Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix and Elvis Presley, had succumbed to their demons to make a comeback sound improbable.

Moreover, the platinum-selling artist became a curiosity, a fish in a bowl in her native London, gawked at wherever she went and inevitably reluctant to go outside.

Journalists who visited her Camden home while she was pining away for the imprisoned Blake spoke of the mess—pizza boxes, food wrappers, beer bottles, clothes and underwear, all living together in disarray. People representing varying levels of devotion, friendship, hanger-on and detriment came and went.

When the racist song video came out in June 2008, she eventually emerged to greet the horde of paparazzi outside her door. “I guess I should apologize,” she said frankly, according to a Rolling Stone reporter who had embedded for the night inside Amy’s three-bedroom home.

Asked what she planned to call her next album, she cheekily replied, “Black Don’t Crack.”

Amy, looking alarmingly thin, told the reporter later that night, “I’m on a strict pizza diet. I’m on a strict put-weight-on diet. I love food. I’m just stressed out.” Evidence of self-harm pockmarked her arms.

People, including her father, speculated that she almost preferred being miserable because it was essential to her creative process.

“It’s a shame,” Mitch Winehouse, who lived with his daughter for a brief period to try to keep her on track after rehab in 2008, told the Sunday Times. “But that’s the way she is. Amy can be creative when most other people would be checking into a hospice. When she can hardly stand up she’s got her books in front of her, scribbling away.”

“Whatever happens,” he predicted, “we won’t be where we are now in two years’ time.”

Fred Duval/FilmMagic

2009 started off promisingly enough, with her sober trip to St. Lucia, some of which is chronicled in her friend Blake Wood‘s 2018 book Amy Winehouse, featuring never before seen photos of the vulnerable star. That March, however, she was charged with assault for allegedly smacking a fan who approached her to take a picture at a festival in September 2008. That thwarted a trip to the U.S. to headline at Coachella because she was denied a work visa due to her ongoing legal issues.

In his 2012 book Amy, My Daughter, Mitch Winehouse wrote that Amy called him on New Year’s Day, 2010, and said she hadn’t had a single drink on New Year’s Eve. She was taking Librium, to help with withdrawal symptoms, and it made her tired.

Winehouse went to Jamaica in February 2010 to work on her third album with Salaam Remi, though she wasn’t satisfied with any of her writing yet. That March she recorded a cover of “It’s My Party” for Quincy Jones‘ Q Soul Bossa Nostra.

At the same time, she was in and out of the London Clinic that spring, half-heartedly trying to get a handle on her drinking.

Yui Mok/PA Images via Getty Images

She also started dating director Reg Traviss, and they notably did not get into trouble together. (Amy’s parents had worried because Blake Fielder-Civil never stopped calling her, and she was forever fretting over getting her ex clean and was prone to drinking after she’d see him, so they were relieved when she met Traviss.)

Mitch wrote that Reg and Amy talked about getting married. “It might have saved her life,” he speculated.

But her drinking would never cease for more than a few weeks, at most.

Dave M. Benett/Getty Images

In May 2010, she was too drunk to make a meeting with her record label and she checked back into the London Clinic for a week. She went back in June. On June 20 she joined her dad (a cabdriver with life-long singing aspirations) onstage for three songs at Pizza on the Park.

She looked healthier than she had in years at Tony Bennett‘s show at London’s Royal Albert Hall on July 1, 2010. She performed at the 100 Club a few nights later with Mark Ronson. She was working out and doing yoga.

That August, she was drinking heavily. In September, however, she looked great, Mitch recalled. In October, she was back on the booze. That December, she pulled herself together and flew to Russia to perform at a private New Year’s Eve party for a billionaire oligarch.

“This is the strongest Amy has felt in a very long time,” a source told MTV UK. “She is determined to go down in history as a world-class performer, not someone who ruined a spectacular talent through drugs. The long road back starts in Moscow.”

“There’s a lot to look forward to in 2011,” Mitch Winehouse remembered writing in his diary.

Winehouse kicked off the year performing at the Summer Soul Festival in Sao Paolo, Brazil, her first full live show since 2008. (Her team reworked her set so that more Frank songs were interspersed amid the heartbreaking Blake songs of Back to Black.)

On Jan. 16, 2011, after her last of five shows in Brazil, she told her dad she hadn’t had alcohol in more than two weeks. Not long after, once she was back in England, Blake Wood (“American Blake,” Mitch called him) called him to say he’d been Skyping with Amy and she’d had a seizure. She had no memory of it, which is apparently not unusual, and Mitch took her to the hospital for observation.

One morning in February, he went to his daughter’s house to find she’d already had multiple drinks that day. But still, he felt, her bad days seemed to be growing fewer and further between.

It was a bad day later that month when Amy was booed onstage in the United Arab Emirates. “Disappointed Dubai fans say no, no, no to rehab singer,” wrote Time Out Dubai.

In March 2011, Winehouse cut herself again, about a week after Fielder Civil was arrested on charges of burglary and firearm possession. (He was sentenced in June to 32 months in prison.)

She also returned to the studio that month to cut a cover of “Body and Soul” for Bennett’s Duets II album, which turned out to be her last recording.

She went back to the hospital in April to be treated for detox complications and she finished the month trying to stick to her program. Then she was readmitted to the London Clinic on May 11, and her blood test showed high levels of potassium and glucose, which the doctor warned could lead to heart problems. She was back to drinking the daylight away on May 24.

Basically, this portion of Mitch Winehouse’s memoir reads like a hospital log, but as told by a distressed, devoted father.

Kevin Mazur/WireImage.com

Winehouse’s last performance was in Belgrade that June, and despite having been largely clean for a couple weeks, she got drunk before heading out onstage for an agonizing show that lasted 15 minutes longer than her usual 75-minute set.

They canceled the rest of her scheduled gigs and she returned to London on June 22. She had turned a sober eye on what happened in Belgrade and again told her dad she “really, really” wanted to stop drinking.

As much as Mitch could tell, Winehouse stopped drinking for the rest of June and when he saw her on July 10 and July 14, she was sober and in good spirits.

On July 20, she went to the iTunes Festival at the Roundhouse in Camden to see her friend and protegee Dionne Bromfield, the first artist signed to Winehouse’s Lioness label, sing and ended up onstage dancing. Months later, Mitch’s manager told him that he’d seen Amy at the show, and that she’d gone up to him, patted him on the stomach and said, “‘Look after my dad.'”

Mitch Winehouse last saw his daughter on July 21, 2011. He was flying to New York the next day but she insisted he come over to look at some family photographs she’d unearthed.

Paul Brown/REX/Shutterstock

“It was easy to be with her that day; she was a lot of fun,” he recalled in Amy, My Daughter.

Janis Winehouse and her fiancé Richard Collins (Mitch and Janis divorced when Amy was 9), and Reg Traviss saw Winehouse on July 22 and she seemed fine to them. That night she was “tipsy,” her security guard Andrew Morris recalled, but she was singing and playing drums in her room.

When Andrew checked on her at 10 a.m. BST on July 23, she appeared to be sleeping. Five hours later, she hadn’t moved.

The knee-jerk guess was that she had died of some sort of overdose.

Officially, she died of accidental alcohol poisoning, or “misadventure,” as the coroner ruled it at the inquest. Her blood-alcohol level was .416 (416 mg of alcohol per 100 ml of blood), with .35 considered a fatal level (.08 is considered too intoxicated to drive). Two large empty vodka bottles and one small were found in her house.

Several days later, Reg Traviss, who took Amy’s cat, Katie, home to live with him, told The Sun, “I can’t describe what I am going through and I want to thank so much all of the people who have paid their respects and who are mourning the loss of Amy, such a beautiful, brilliant person and my dear love. I have lost my darling who I loved very much.”

“She did not want to die,” her personal doctor, Dr. Christina Romete, who had treated her at the London Clinic, said at the inquest that October. “She was looking forward to the future.”

In a statement, the family, which did not dispute the findings, said, “We understand there was alcohol in her system when she passed away—it is likely a build-up of alcohol in her system over a number of days.

“The court heard that Amy was battling hard to conquer her problems with alcohol and it is a source of great pain to us that she could not win in time.”

Before she was cremated, about 500 people attended a prayer service in the hall at Edgwarebury Jewish Cemetery, which ended with the playing of Carole King’s “So Far Away.”

Blake Fielder-Civil told Pigeons and Planes in 2016 that he was allowed to have a small prayer ceremony for Amy in the prison chapel when she died.

“Body and Soul” was released on what would have been Amy’s 28th birthday. Lioness: Hidden Treasures, a compilation of unreleased tracks and demos, came out in December 2011. The following February, she was posthumously awarded the Grammy for Best Pop Duo/Group Performance with Bennett. Another Grammy nomination came in 2013, Best Rap/Sung Collaboration, for Nas‘ “Cherry Wine,” which was dedicated to her and featured her vocals.

As Lady Gaga said on The View, the think pieces poured forth about addiction and the perils of fame. But it’s unclear if anything registered about how to treat our young super-stars, most of whom are more intertwined than ever with their fans thanks to social media and prey to the whims of online feuds and outrage culture. It was a lot when Amy was alive, and it’s more now.

Ultimately, Winehouse’s death was a tragic accident, albeit one that seemed eerily inevitable. She’s been posthumously humanized more than most with the help of her family, and, any controversy aside, projects like the 2015 Oscar-winning documentary Amy. Yet while the appreciation for her musical output is endless, we’re also left with an even greater sense of just how unfairly preordained her death turned out to be. Fans adored her music and wanted more from her. But at the same time, people also ended up expecting her to implode—almost in a cartoonish, TV-death sort of way, as no one was actually hoping that would happen—and then she did. Her 27-year-old body couldn’t take it anymore.

The unhappy ending people expected is exactly what they got.

Amy Winehouse propagated her own myth of the irreparably damaged artist from the beginning, telling The Guardian in 2006, “If you’re a musician and you have things you want to get out, you write music. You don’t want to be settled, because when you’re settled you might as well call it a day.”

So we’ll never know if Amy Winehouse would have eventually realized that the two didn’t have to be mutually exclusive, that perhaps one day she too could be “settled” without creative consequence. In the meantime, she didn’t suffer for her art so much as figure that, since she was suffering, she may as well make art.

She told E! News in 2007 that she didn’t care if she was getting a reputation for being difficult, or that her personal life was making headlines. “I’m above it,” she said. “I really like my record, you know. I’m really proud of it. If 10 other people like it, I’m happy.”

(Originally published Sept. 14, 2018, at 3 a.m. PT)