We see the accomplishment listed among the best novels: just above the title or the author is the disclaimer “New York Times Best Seller” or “New York Times Best-selling Author.” But according to recent reports, nobody knows the inner workings of what exactly makes a book a bestseller on this list outside of those who work for The New York Times.

According to the NYT themselves, “The weekly book lists are determined by sales numbers.” And that’s pretty much all they have to say about that, at least on the record. They say it takes into account sales numbers from all kinds of retail storefronts, be they big box stores, online retailers, or independent bookstores. But ever since the NYT Best Seller List made its debut in 1931, there’s been rumblings in the literary world of certain authors attempting to hack the system and “buy” their way onto the list.

According to an Esquire report from last year, the NYT has long denied using resources like ReaderLink or BookScan to accumulate sales numbers, since they aggregate data. They also only typically look at sales numbers from Amazon and other giant chains like Walmart or Target. Using resources like these would take away from the contribution of individual sales accrued at independent bookstores or specialty stores, and are therefore easy to manipulate.

“To my knowledge, The New York Times tracks sales of books, and the sales are what is ‘supposed to’ decide where those books sit on the list. However, the truth is, it’s much more editorialized,” stated a literary publicist quoted in the Esquire report. “There is quite a bit taken into consideration — i.e., are the book sales mostly bulk buys? Are they mostly indie bookstore sales? Are they mostly Amazon sales? Even which list the book would be considered for has a huge effect.”

In 1995, The New York Times Best Seller List introduced the dagger symbol, which indicates a book that has been bought in bulk and whose sales might not accurately represent its standing as a bestseller. This came after Michael Treacy and Fred Wierserma were accused of having spent a quarter of a million dollars that year on copies of their own book, The Discipline of Market Leaders.

Buying or hacking your way onto The New York Times Best Seller List is something afforded to the rich and privileged, specifically those with significant amounts of white privilege. Indeed, one need not look far for numerous lists of right-wing American politicians who have attempted to tip the commercial sales in their favor more than once after they’d published a book. The same can be said for reality television stars who have been accused of buying their way onto bestseller lists: they are almost always white and come from money.

It’s only natural that some authors, looking more to prioritize profit over the value of their so-called art, would try to hack the system. Here are some noted instances of people trying to buy their own way onto The New York Times Best Seller List.

Authors Who Have Tried to Hack The New York Times Best Seller List

Trump: The Art of the Deal by Donald J. Trump

What? The twice-impeached disgraced former President of the United States once tried to influence the sales of his 1987 memoir and business advice book, The Art of the Deal? I’m shocked. According to Trumped!, the 1991 tell-all by former Trump employee Jack O’Donnell, The Art of the Deal only became a bestseller because of the author’s organization buying tens of thousands of copies themselves. In his book, O’Donnell recalls buying 1,000 copies of the book at the gift shop in the Plaza Hotel, only to be told by a fellow employee that it wasn’t nearly enough. He needed to order 4,000 copies.

Real Marriage: The Truth About Sex, Friendship & Life Together by Mark & Grace Driscoll

This book is just one of many that’s hacked its way onto the NYT Best Seller List by way of a marketing or consulting firm hired to guarantee its spot there. Mark Driscoll, a megachurch pastor, spent US$210,000 to get Real Marriage to the number one spot on the list in 2012. It wasn’t until 2014 when how it got there was revealed; Driscoll wrote an open letter to the public apologizing for his actions, claiming he would no longer refer to himself as a New York Times best-selling author and would set out to rectify the situation. But it was too late for some in the evangelical community, who wrote him off for good.

Next Level Basic: The Definitive Basic Bitch Handbook by Stassi Schroeder

Known for her appearances on the reality television series Vanderpump Rules, Stassi Schroeder published her first book Next Level Basic in 2019, followed by her second Off with My Head in 2022. Both appeared on The New York Times Best Seller List…but with a dagger symbol next to them, indicating that the sales of the book that had been recorded had benefited from bulk purchases. This should not come as a huge surprise for either title, given that it’s pretty on brand for a self-proclaimed “basic bitch” to manipulate her own sales. Plus her second book is supposedly a manual for what to do when you’ve been “cancelled,” as Schroeder was fired from Vanderpump Rules after displays of racist behavior towards another cast member. And no one wanted to buy that book? Another shocker!

Valley of the Dolls by Jacqueline Susann

While this novel would become something of a cult classic in its ensuing decades, its initial success in commercial sales despite predominantly poor reviews of Valley of the Dolls could have something to do with its author. Jacqueline Susann, an actress turned novelist, would have stopped at nothing to ensure the success of her new career in books. Therefore, it’s been widely reported throughout the rest of the 20th century that the new author had a knack for buttering up booksellers who were known to report sales data to the NYT at the time, as well as buying large amounts of her own book with her own money.

A Time for Truth by Ted Cruz

Hmm, interesting title for a book whose bestseller status was less than truthful. In 2015, The New York Times ran into trouble when they distinctly left Ted Cruz’s A Time for Truth off their Best Seller List, despite it having sold nearly 12,000 copies in its first week. The Times claimed that they have certain standards for their famous Best Seller List, and Cruz’s book did not meet those standards. When probed further, the newspaper admitted that it was left off the list because of the large amounts of bulk purchases that had been attributed to A Time for Truth. Then it came out that Cruz had given over $120,000 to his own publisher, likely to buy copies of his own book. He then tried to sell them on his own website for $85 each. No thank you, Ted!

No Apology by Mitt Romney

Oh look, another Republican politician trying to screw the system in his favor! I am, once again, shocked! At least Mitt Romney tried to get creative with buying his way onto the Best Seller List: instead of buying up copies of his own book, he bartered for sales. While on his 2015 book tour for No Apology, he asked for the money corporations would have paid him to speak to be spent on copies of his book. A little less dishonest than buying copies of your own book verbatim, perhaps, but still no less immoral. The Times agreed, using the dagger symbol next to No Apology on the Best Seller List, to denote bulk sales.

I, Libertine by Frederick R. Ewing

In 1956, long before The New York Times was forced to intervene in sales manipulation, a DJ by the name of Jean Shepherd hatched a plan to prove that the NYT Best Seller List was bogus. He had a late-night radio show on WOR in New York, where he baptized his listeners as “night people” who were different from the “day people” folk. “Day people” were phonies and squares who were victims of society’s complacency, I guess. The idea for the hoax that would become I, Libertine began after Shepherd visited a bookstore and when he couldn’t find the title he was looking for, the clerk informed him that it might not exist, since it’s not on any list he’s ever seen. That’s when Shepherd really became convinced that New York, and the world at large, ran on lists.

“The people who believe in these lists are asleep,” he told his listeners. “Anyone sitting up at three in the morning secretly has doubts. What do you say tomorrow morning each one of us walk into a bookstore and ask for a book that we know does not exist?” So I, Libertine was born, written by retired Royal Navy Commander Frederick R. Ewing. Booksellers were so confused by the floods of requests for a book that could not be found. A writer at The Washington Post eventually figured out it was a hoax, and called Shepherd for comment. He conceded to the ruse and exposed the entire story for the newspaper on August 1, 1956.

But it didn’t end there: after all hell broke loose with The Washington Post expose, Shepherd was informed that Ballantine Books was scrambling to get the paperback rights to I, Libertine. Huh? Turns out the hoax had become so popular that Shepherd, sci-fi author Theodore Sturgeon, and the Ballantine publisher put their heads together to produce an actual book called I, Libertine published under the name Frederick R. Ewing. And guess what? It made the NYT Best Seller List.

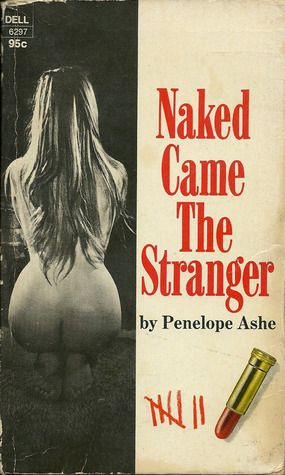

Naked Came the Stranger by Penelope Ashe

Following the popularity of Jacqueline Susann’s Valley of the Dolls in 1966, Newsday editor Mike McGrady decided to try his hand at what he believed was the novel’s formula for success. He decided to try to trick The New York Times Best Seller List by producing a novel with “ironic commentary” that spoke to the public’s appetite for Susann “and her ilk.” He sought out to create a committee that would write this future bestseller. “As one of Newsday’s truly outstanding literary talents, you are hereby officially invited to become the co-author of a best-selling novel,” he wrote to his colleagues. “There will be an unremitting emphasis on sex. Also, true excellence in writing will be quickly blue-penciled into oblivion.” Twenty-four writers signed on to the project, and it was published as Naked Came the Stranger under the name Penelope Ashe in 1969. It sold 200,000 copies before the hoax came out, and that only increased the book’s popularity: it stayed on the NYT Best Seller List for another 13 weeks after that. Unlike I, Libertine, Naked Came the Stranger is a real book, just one that was commissioned under less than organic circumstances.

Have you heard of other stories of authors buying their way onto The New York Times Best Seller Lists?