The place where the lost things go isn’t one of the most frequently-occurring story tropes, but it’s certainly one of the more compelling. In the Wizard of Oz universe, L. Frank Baum created the Valley of Lost Things, a location in Merryland where anything lost in the real world will eventually turn up. Danielle Page expanded on Baum’s concept in her Dorothy Must Die series, giving us the Island of Lost Things, a place that travellers can only find if they get totally lost on their journeys. There are contemporary spins on the concept — Stephen King’s Finders Keepers focuses on a lost collection of notebooks — and versions tied to particular locations or types of lost object, such as Un Lun Dun by China Miéville, home to everything lost in the city of London.

What is it about places where the lost things go that bring us back again and again? Part of the reason is that, undoubtedly, this is something we can all relate to on a personal level. We’ve all lost something in the past that we really regretted, and in many cases, still miss — particularly beloved childhood toys, which are often the first things found by heroes who reach the places where the lost things go. When characters in stories find their own lost things, it takes us back to possessions — and people — that we may have lost in the past, and makes us wonder if, somehow, they’re still around somewhere. But our fascination with lands of lost things doesn’t stop there. Like the possessions found in them, there’s much more to lands of lost objects than meets the eye.

Lost and Found

Lands of lost things serve an interesting purpose in stories, serving both the plot and the characters. Humans have a tendency to anthropomorphise our belongings, and imagining a place where our beloved old friends are being kept safe until we can find them again is a way of dealing with the sadness, guilt and sometimes grief we feel at losing them. Lands of lost things, whatever form they take, all have a similar purpose — they give the characters, and by proxy the reader, the opportunity to find some kind of catharsis over lost things from their childhood. They can also give us the hope — often in vain, but sometimes not — that we might find our own lost things again.

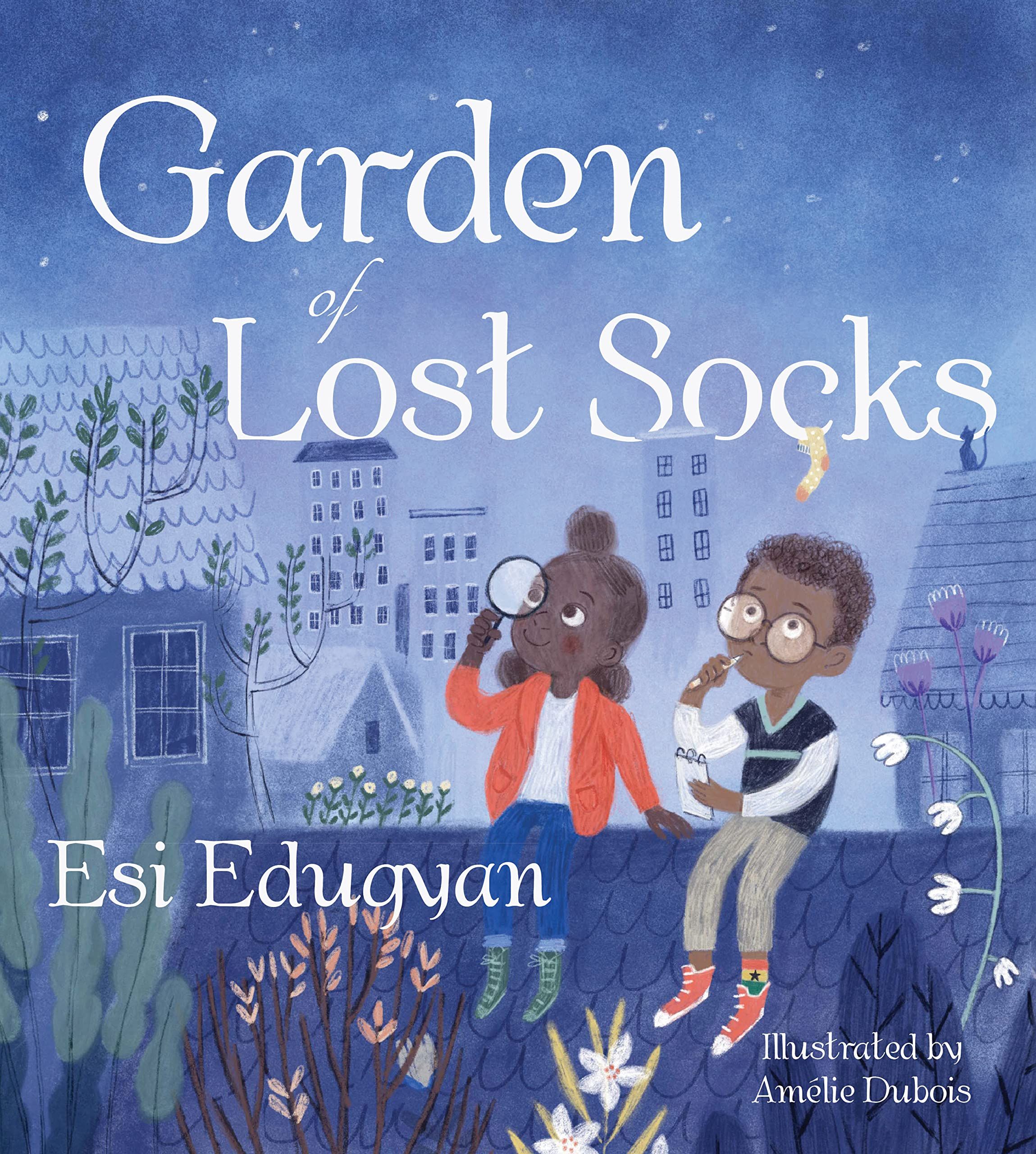

There’s also the fact that the action of travelling to a land of lost things, whether it’s the real destination or a stop along the way, is a classic story hook. Many stories are built around a journey to hunt for treasure — and what could be a more important treasure than something you loved when you were young, or something that you still miss no matter how many years have passed since you lost it? Authors can also heighten the peril of a story by exploring other, more dangerous lost objects — or sometimes creatures — that have found their way to the place where lost things go. Finding lost things is the central plot of Garden of Lost Socks by Esi Edugyan and Amélie Dubois, a story about a young girl, Akosua, an ‘Exquirologist’ who devotes her time to finding lost things in her community with her new friend.

The Different Lost Lands

While lands of lost things are all built along the same kinds of principles — lost objects, creatures and people being mysteriously transported to a place where they’re collected together, ready to be rediscovered — the way these places are constructed can often vary greatly. Some lands of lost things are full of a miscellany of everyday objects, like the Valley of Lost Things in Baum’s book, which is mostly filled with pins, buttons, thimbles, and other easily-lost small objects. Un Lun Dun, as I already mentioned, is a twisted reflection of the real-world London, full of the citizens and objects that the real city has let fall by the wayside. Others are a lot more specific — for example, in A Place Called Here by Cecelia Ahern, the heroine finds herself in a place where all the lost people go, something that gives her a chance to reconcile feelings about people she has parted ways with in the past. Some of the places full of lost things are benign, while others are more sinister. The joy of finding lost things can be tempered by the realisation that the hero, or heroes, are lost themselves, and have to fight to find their way home.

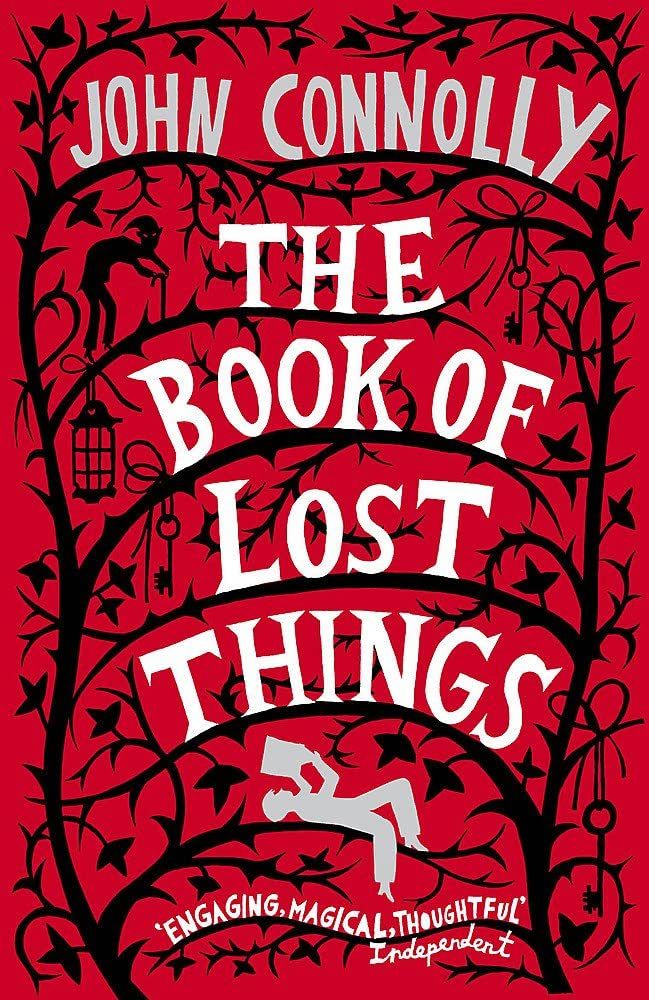

Searching for lost loved ones in a land of lost objects is a classic twist on the premise, and one that can make for a bittersweet story. While not a traditional land of lost objects, the fairy tale world in The Book of Lost Things by John Connolly is inspired by the concept — it’s a place where the protagonist, David, hopes that he will be able to find his dead mother, although journeying through the dangerous fantasy world makes him realise that life is sadly not that simple. Similarly, in The Keeper of Lost Things by Ruth Hogan, protagonist Anthony is curating his own land of lost things by collecting and labelling everything he finds, as part of his lingering grief over his late fiancée. We often keep our deceased loved ones close by holding onto objects that belonged to them, and lands of lost things can often serve a similar purpose in stories, by providing something tangible that the protagonists can sift through and spark memories of their pasts.

Lands of lost objects can be used as a metaphor for grief or to explore material loss, but they can also be a way of looking at more nebulous human conditions. In Perduo: Obadiah Emerson in The Place Where Lost Things Go by Robert E. Berge, Obie, an adult in his 30s who has no idea where his life is going, finds himself in the land of Perduo, a land of lost objects that has been warped by the work of a dastardly corporation. Obie’s journey to Perduo happens in large part because his own lack of direction in life, but while many stories use lands of lost things to help characters find themselves, Perduo takes a darker and more satirical look at why so many of us feel lost in the first place. This can be a flip side of lands of lost objects — while we may be able to find our lost books, toys or companions, it’s not so easy to find feelings, interests or motivations that we’ve lost over the years.

However lands of lost objects manifest themselves in fiction, they always provide a compelling mystery that keeps the protagonists and the plot moving, and draws the reader further into the fictional world.

For more stories that walk the boundaries between fantasy and mystery, try 8 Magical Mystery Books to Get Lost In. If you want to read more about the world of Oz, try The Wonderful Wizard of Oz: What the Movie Got Wrong.