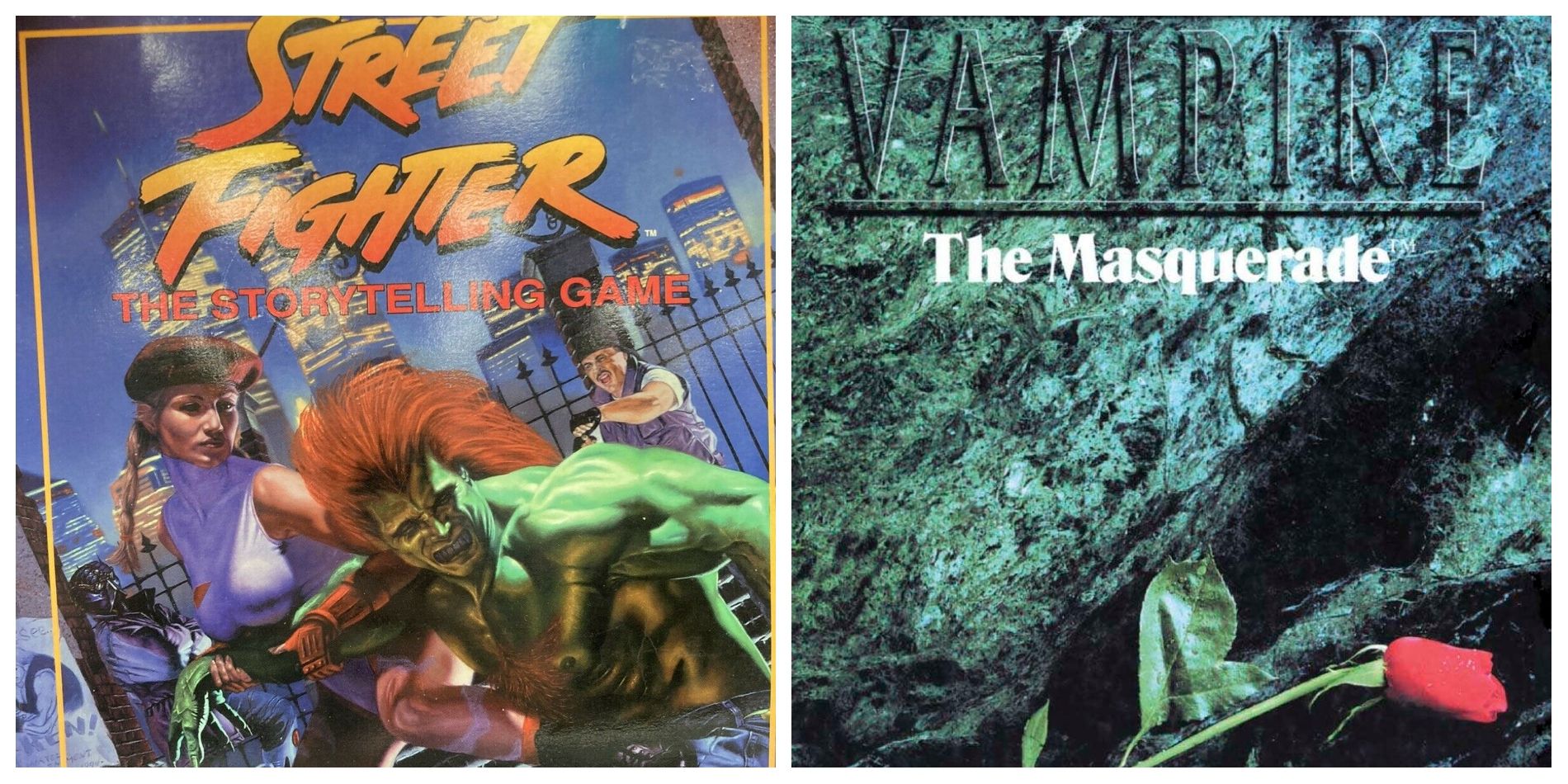

The iconic Street Fighter character Ryu has one dot in computers and two dots in drive. This bit of trivia might not synch up with any other Street Fighter media, but it comes from Street Fighter: The Storytelling Game, an interesting but short-lived tabletop RPG. The Street Fighter TTRPG was produced by White Wolf Publishing, the creators of Vampire: the Masquerade and its related World of Darkness line of tabletop RPGs, and it shared the same mechanics, using a modified version of the Storyteller System. The World of Darkness system was not an intuitive match for Street Fighter, with its focus on drama over complex combat, but it did make for a unique RPG experience, as one of the earlier intersections of video games and tabletop RPGs.

At the time of the Street Fighter TTRPG‘s release, White Wolf had already found success with Vampire, Werewolf: The Apocalypse, and Mage: the Ascension. These games took place in a shared world, and used the Storyteller System, which provided much simpler game mechanics compared to many other RPGs of the era, like Advanced Dungeons & Dragons’ 2nd edition. The game used much lower numbers than D&D, with traits and skills typically rated from one to five, and a relatively simple system of adding up a trait and a skill, rolling a number of ten-sided dice equal to that total, and counting successes. There was less focus on combat in Vampire: the Masquerade and its sibling games than D&D and other mainstream RPGs.

Adapting the Street Fighter video games may not have been an ideal fit for a system built around social interaction and investigation as much as battle. Characters built in the Storyteller System divided traits between physical, mental, and social attributes, but for professional tournament fighters, physical attributes were the obvious priority. Characters as disparate as Ryu, Blanka, and Dee Jay were shown as having all fives for their physical abilities on their character sheets.

The Street Fighter RPG Was Odd, But Also Ahead Of Its Time In Ways

The tabletop game did make some modifications to the system to account for the combat-focused nature of the Street Fighter license, however. Many characters had the option to extend attributes beyond the normal human maximum of five, an option normally reserved for the like of elder vampires and raging werewolves in the World of Darkness games. New scores were added for chi and honor, and players could create their own World Warrior using a variety of fighting styles based on Street Fighter game characters. The system also added special moves, like Ryu’s hadoken and dragon punch, as well as favored combo attack maneuvers, extending unarmed fighting beyond simple options like punch, kick, and tackle, featured in the mainline World of Darkness games.

Street Fighter: The Storytelling Game also included novel options of combat cards for attacks, as well as more emphasis on tactical movement than the typical Storyteller System game. The book included several example adventures with maps, more reminiscent of D&D modules than a typical World of Darkness game, using hex grid movement rather than the square grid of D&D. Thirteen years later, 4th edition D&D would emulate some aspects of the Street Fighter TTRPG, as it also relied heavily on grid map play, incorporated a system of powers that resembled the special moves of games like Street Fighter, and cards for various classes’ powers were sold as supplemental aids for players.

Street Fighter: the Storytelling Game is out of print, but despite being an oddity at the time of its release, the game was fairly forward thinking in many ways. RPGs based on video game licenses have made a resurgence recently, with games like Dragon Age and Dishonored making the transition to tabletop play. The Street Fighter TTRPG’s streamlined mechanics made a potentially cumbersome combat system fast and easy to learn, and its tactical elements made movement and positioning more relevant than other White Wolf games. The lore drew mostly on Street Fighter 2, as it was released prior to the Street Fighter Alpha series and Street Fighter 3, leaving setting details fairly sparse.

While it was lacking in some areas, those who had a chance to play this obscure game experienced a TTRPG that worked better than it had any right to, and foreshadowed both the future of Dungeons & Dragons, and the later resurgence of video game-based RPGs. Admittedly, licenses with elaborate fantasy settings, like Dragon Age, are more intuitive fits for this format, but considering the challenge of turning a fighting game like Street Fighter into a playable and enjoyable RPG, with compelling drama inside and outside the ring, this early White Wolf product holds up surprisingly well.

About The Author