Pascal Rondeau/ALLSPORT/Getty Images

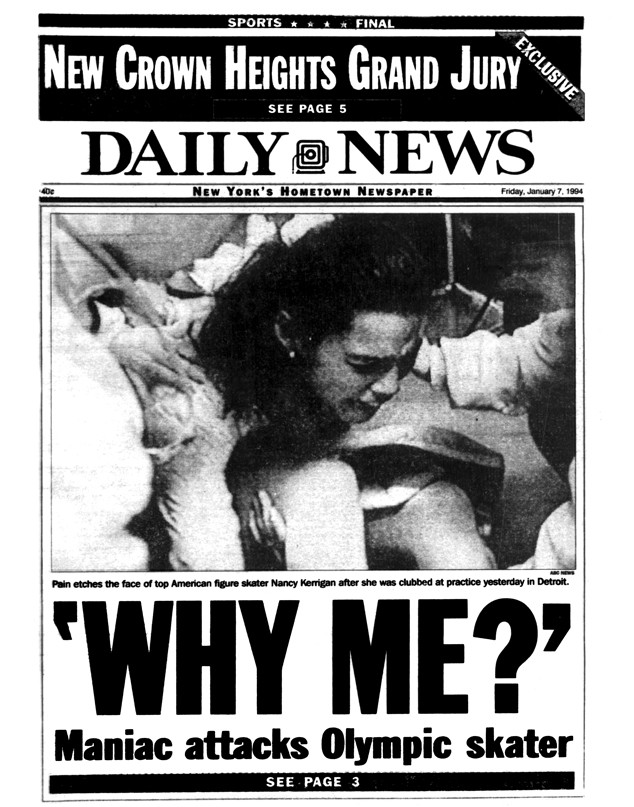

“Why?! Why?!“

Screams rang out at around 2:35 p.m. on Jan. 6, 1994, after Nancy Kerrigan‘s practice session at Detroit’s Cobo Hall, which was right next to Joe Louis Arena, site of the U.S. Figure Skating Championships.

The tearful cries were coming from Nancy herself. The 24-year-old athlete, due to skate the following night in the ladies short program, had been on her way to the dressing room when a man approached, hit her several times on the right knee with what looked like a pipe or crowbar—”some hard, hard black stick,” Kerrigan sobbed—and fled. “Help me!” she yelped.

Daniel Kerrigan, Nancy’s father, picked up his crying daughter and carried her into the locker room, where she was examined and then taken to a nearby hospital for X-rays. Swelling in her bruised knee forced her to withdraw from the competition, but luckily nothing was broken.

“I just don’t want to lose faith in people,” Kerrigan told ABC Sports after the extent of her injuries was known. “…It was one bad guy and I’m sure there’s others because this kind of thing has happened before in other sports…Most people are worried about me, wondering what happened. Those are the people that I want to tell I’m okay.

“It’s not the most important thing—skating—so if I can’t [skate] I’ll have to deal with it. It could have been a lot worse.”

In April 1993, American tennis star Monica Seles had been stabbed on the court after a match in Hamburg, Germany, by a deranged fan of German player Steffi Graf. Seles healed physically within weeks, but the terrifying attack kept her away from the game for two years. Asked for comment in the wake of what happened to Kerrigan, Seles said in a statement, “Crimes against us are more public but no more tragic than what happens to too many innocent victims today. My thoughts are with Nancy, and I sympathize with the shock and horror she and other victims of senseless crimes experience.”

“He was clearly trying to debilitate her,” Dr. Steven Plomaritis, who treated Kerrigan’s knee, said of the as yet unknown assailant.

AP Photo/Lennox McLendon

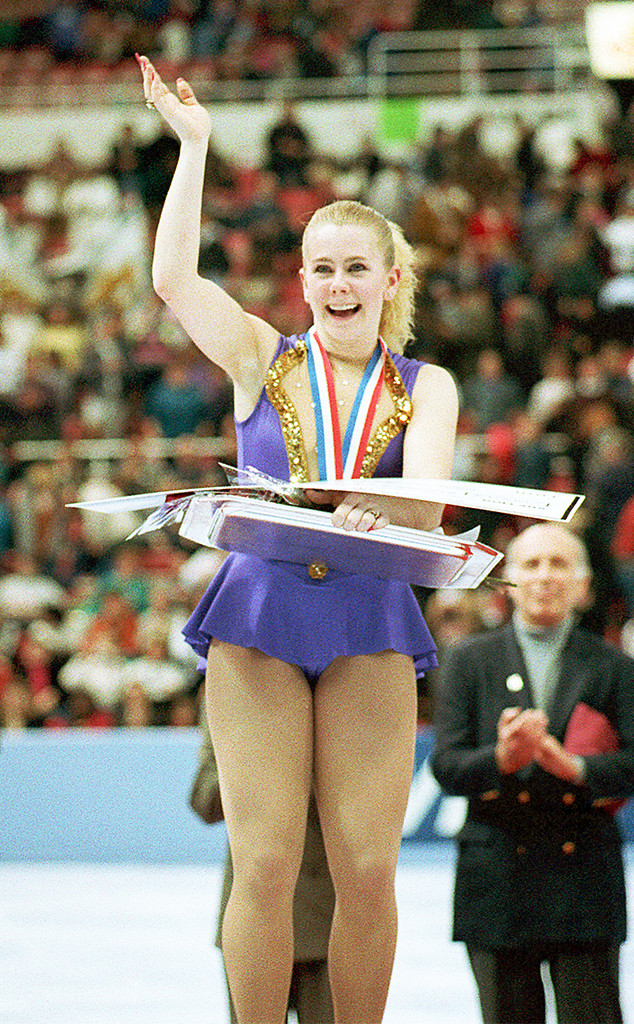

Tonya Harding, from Portland, Ore., topped the leaderboard after the short program the next night.

Meanwhile, U.S. Figure Skating, the sport’s governing body, had a decision to make, whether or not to reserve one of the coveted spots on the U.S. Olympic team for Kerrigan, relegating whoever finished in second place that weekend to alternate status. As it stood, you had to compete in the U.S. Championship to be considered for the Olympics—or so they thought. The rulebook actually said no such thing, which a Newsweek reporter swiftly pointed out.

“I think we’d accept graciously if they send Nancy,” Kerrigan’s coach Kathy Casey told reporters after the attack. “She’s paid her dues, she’s come back strong this year. If they choose to do that, I think we’ll probably have our strongest team.”

Harding said, “It’s not my decision to make. If they decided not to take me, I’d accept that.” (The skater had actually pulled out of a tournament in her hometown the previous November after she said she had received a death threat, putting her and Kerrigan in a similar boat as far as early accounts of the Kerrigan attack framed the potential perils these athletes were facing.)

But Harding, the first American female skater to land a triple axel in competition three years prior, went on to win the U.S. championship that weekend, a triumph that assured her a spot on the team going to Lillehammer, Norway, in February.

Ultimately Kerrigan’s prognosis was good, so she too made the team, and Michelle Kwan, who finished second in the U.S. finals, was the alternate. Kerrigan and Harding were previously Olympic teammates in Alberta, in 1992, where Kerrigan earned a bronze medal and Harding finished fourth. (1994 was the first year the IOC split the Winter and Summer Games into separate years, hence only a two-year gap between Winter Games on this occasion.)

Six days after Harding won in Detroit, three men were arrested in connection with the attack on Kerrigan. One of the men, 26-year-old Shawn Eric Eckardt, had a criminal record and had worked as Harding’s bodyguard.

In custody, he alleged pretty much right away that Harding was involved in the planning and subsequent cover-up of the attack (which, police had discovered by then, had been perpetrated with a collapsible metal baton that had been found in a trash can behind the arena). Eckardt told authorities he had hired Derrick B. Smith, 29, to carry out the attack, and Smith in turn got his nephew, 22-year-old Shane Stant, to actually commit the act.

Harding’s ex-husband, Jeff Gillooly, with whom she had since reconciled and was again living with, confirmed he was also under investigation. He was arrested on Jan. 19.

Per court documents filed in the case against them, the four men who’d been arrested met at Eckardt parents’ home in Portland in December 1993 to plan the attack—which Gillooly said should target Kerrigan’s “landing leg.” Smith and Stant were going to be paid $6,500 to attack Kerrigan when she was practicing in Boston, but they didn’t get a chance, so they went to Detroit. On Dec. 27, Gillooly gave Eckardt $2,000 in cash, which Eckardt gave to Smith. Eckardt then wired $750 to Smith on Jan. 4. Smith got another $1,300 from Gillooly via Eckardt on Jan. 6.

“When we read the transcripts of the 10 hours of depositions they gave, you did have to laugh,” Kerrigan later told USA Today, acknowledging that even she found something to laugh at in the story of the bumbling criminals. “It was definitely humorous at times. They came to Boston and forgot their IDs and money so they couldn’t really get anywhere. You laugh in thankfulness that they were not as good at being bad guys as they had wanted to be. It all sounds ridiculous, which does make you laugh.”

Kerrigan, speaking to reporters in the driveway of her parents’ house in Massachusetts, said in response to the shocking reports of the alleged plot, “I can’t understand any explanation of why something like this would occur. I don’t think I could ever understand the answer, because I can’t think that viciously.”

Asked about the prospect of going to the Olympics with Harding, she answered curtly, “I have nothing to say about her.”

Officials basically hoped that Harding would voluntarily withdraw from the team. She insisted she had nothing to do with what happened, but in a tearful Jan. 27 news conference she admitted to learning the details after the attack. When word got out that US Figure Skating was looking to suspend her, her lawyers threatened a $25 million lawsuit if she was prevented from going to Lillehammer.

ERIC FEFERBERG/AFP/Getty Images

The resolution decided upon was that neither side would go on the offensive, and Harding and Kerrigan both went to the Olympics, where all eyes were on them.

“I could have gotten straight 6.0s [perfect marks at the time] in the Olympics, and people would have asked, ‘Well, what are Tonya and Nancy doing?'” 1988 figure skating gold medalist Brian Boitano, who beat considerable odds to make the U.S. men’s team in 1994, told NBC News earlier this year, discussing the madness of that time 25 years later.

“In retrospect, it was good for most of us,” he added. “It catapulted skating to another level of interest, one that it will never get back to. I was able to work at a high level for many more years to come.”

Jerome Prevost/TempSport/Corbis/VCG via Getty Images

Harding’s lackluster but also dramatic showing, with her 10th-place finish in the short program and her too-short laces and subsequent do-over in the free skate, are well documented. She finished eighth overall.

Kerrigan was in first place heading into night two, and audiences around the world held their breath as she took the ice—and, happily, turned in a nearly spotless performance, executing only a double instead of a planned triple flip for her opening jump.

“A true test of courage that she passed with flying colors,” one of the TV commentators said as a Vera Wang-clad Kerrigan raised her arms in triumph at the end of her long program, beaming at the applause.

“I can’t have any disappointment, that part’s up to judges and I skated great—considering where I was a month and a half ago, it’s unbelievable,” she told CBS Sports after finishing her routine.

Mike Powell/ALLSPORT/Getty Images

Kerrigan’s performance was only exquisite enough for silver, however, while Ukraine’s Oksana Baiul won the gold.

“I was smiling. I was happy. I was enjoying myself,” Kerrigan, who had blinked back tears earlier, said as the night drew to a close. “I did the elements. I showed how strong I am, how mentally strong I am. How can I complain?”

And with that, Kerrigan and Harding’s paths diverged for good, though both journeys were shadowed in different ways by the seven weeks when their lives were inextricably linked.

They had already been painted into opposite corners, Harding the scheming, kinda trashy villain and Kerrigan the graceful heroine who bounced back with aplomb from the potentially devastating attack on her landing leg.

Adam Butler/PA Images via Getty Images

Not to say that Harding didn’t have her stalwart supporters leading up to the Olympics (and beyond), including many from her hometown who rallied behind her, sporting “We Believe Tonya” buttons and reminding the interlopers from the national (and international) news media that she was innocent until proven guilty. People rose at dawn to watch the overnight tabloid sensation’s practice sessions, dreams of Olympic gold twirling in all their heads.

And whether they believed wholeheartedly in her innocence or were convinced of her guilt—that surely she had something to do with the attack before the fact—many attributed Harding’s sorry situation to her abusive, impoverished upbringing; her messy marriage, which included two restraining orders filed against Gillooly, and subsequent divorce; and any other lifestyle hardships that may have contributed to bad decision-making on her part.

At the opposite end of the reactionary spectrum, it was reported that Kerrigan signed an estimated $9.5 million in endorsement deals in the month between the attack and the Olympics.

Kerrigan rode in a parade at Walt Disney World, hosted Saturday Night Live and got slimed at the Nickelodeon Kids’ Choice Awards. She signed up to do a 15-city Christmas on Ice Tour.

Yet at the same time, that silver was tarnishing at a rapid pace.

NY Daily News via Getty Images

At the parade, Kerrigan was overheard telling Mickey Mouse, “This is dumb, I hate it. This is the corniest thing I’ve ever done.” She insisted afterward that she meant having to wear her medal was corny, that of course she loved Mickey and Disney. Her SNL appearance was panned, though in hindsight she was just as good as numerous male athletes who’ve landed the gig over the years. Her reaction to the slime wasn’t jolly enough for critics’ tastes. Her tone at the Olympics was re-examined, with some concluding that she actually didn’t sound all that gracious. Even her behavior seconds after being clubbed in the leg was subject to second-guessing.

“People made such a big deal and almost, like, complaining, like, why would I say that?” Kerrigan told ABC News in 2017, referring to her memorable shriek of “why?” “Well, after getting attacked, you don’t know what you’re going to say. But I think it’s a reasonable question. Like, ‘Why did this just happen? What happened? Like, why?'”

It was as if the court of public opinion was just waiting until after the Games to give Kerrigan hers, while it had taken care of Harding beforehand. Nancy Mania turned into Nancy Overload, which turned into No More Nancy.

A planned movie project about her life didn’t pan out, while the TV movie Tonya & Nancy: The Inside Story, which aired that April (staring Heather Langenkamp, of Nightmare on Elm Street Nancy fame, as Kerrigan), craftily made the media’s treatment of the scandal the focus of the action—an unwitting precursor to the acclaimed 2017 film I, Tonya, which was an inspired-by-truth take on what happened but also a thoughtful probe of how Harding’s journey was much more complicated than almost anyone stopped to think about in 1994.

Like Harding, Kerrigan more or less had to fend for herself, image-wise over the last 25 years, and though time painted a rosier glow for her, she hardly skated away from Jan. 6, 1994, unscathed. No one may have put them in the same boat in 2017, when the awards season hoopla surrounding I, Tonya—which included an award season sweep for Allison Janney for her brutal portrayal of Harding’s mother—altered the takeaways from that story, but both ’90s era stars had been through the wringer of scrutiny.

“She claims to be unprepared and uncomfortable with celebrity, yet does nothing to avoid it,” read a December 1994 Chicago Tribune analysis of Kerrigan’s flagging star (written in the wake of her Christmas on Ice Chicago stop being canceled). “It’s like a deal with the devil, which one can take or leave but not complain about once it is made.”

The male writer wasn’t lambasting Kerrigan, per se, but rather pointing out that, while arguments that expectations of her to be superhuman were unfair, the figure skating world wanted a superhuman superstar, and perhaps Kerrigan just didn’t fit the bill in the end. (Interestingly, he mentioned golf as another sport that expects more from the conduct of its stars than other sports, less than two and a half years before Tiger Woods won his first Masters—and almost 15 years before Woods proved himself to be not the man golf thought he was.)

Dan Callister/Shutterstock

“I didn’t ask for the special podium people put me on,” Kerrigan recalled to USA Today in 2017. “I was put in the spotlight, and people looked at everything I did. I didn’t ask for that, any of that.”

But life went on.

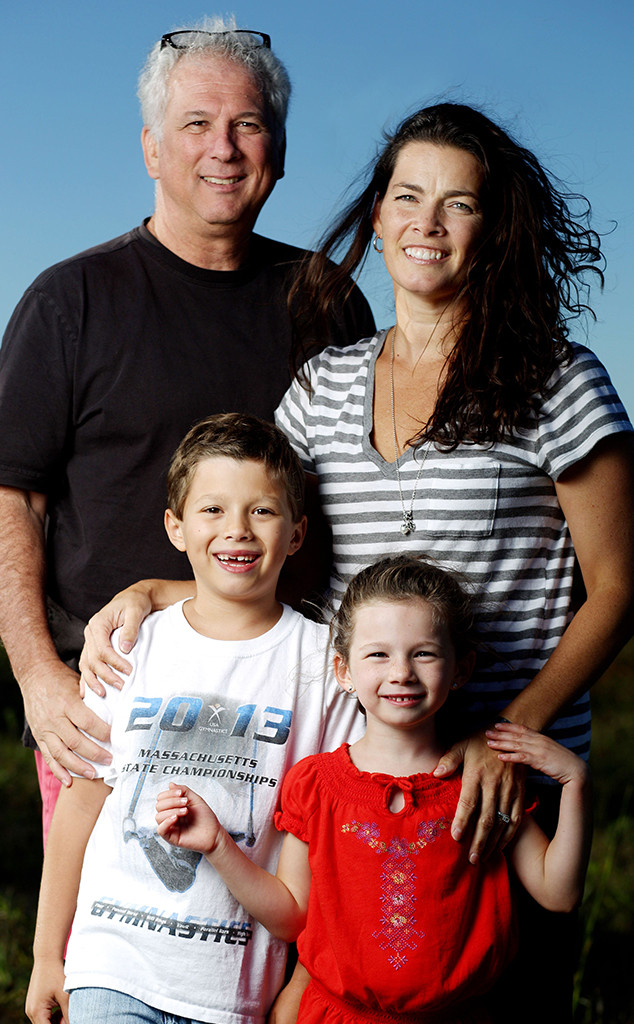

Kerrigan married her agent, Jerry Solomon, in 1995 and they have three children together. “I drive and cook and clean,” she said on Today in 2013. “That’s basically what I do now.”

Her family had suffered a bizarre tragedy in 2010 when her father, Dan, died suddenly of a heart attack and her brother Mark—an Army veteran who had struggled with mental health issues and substance abuse and spent time in jail for domestic abuse—was charged with assault and battery for a drunken, bloody attack on their father just hours before his death.

Mark Kerrigan was barred from his father’s funeral and ended up being charged with manslaughter; he was found not guilty of the more serious charge at trial in 2011 but was convicted of assault and battery. He was sentenced to the maximum penalty of two and a half years in prison, despite his sister’s plea to the judge that he send Mark home to his family, who had stood by him throughout. He was paroled in 2012.

Eric McCandless / Walt Disney Television via Getty Images

“He shouldn’t have been charged,” Kerrigan said on Today. “My dad had a heart attack and that’s that. Since then, we did the same thing we’ve always done—take things one thing at a time, and you get through it. Life’s challenging and hard, and we stick together and move on.”

When she competed on Dancing With the Stars in the spring of 2017, Kerrigan opened up about battling an eating disorder for years after the Olympics. She also revealed that she had suffered at least six miscarriages after the birth of her first child, son Matthew, in 1996, and it was eight years before their second child was born.

Kerrigan finished seventh on the show, but her reemergence was a timely reminder of her experience in the tabloid trenches.

Harding was banned from competitive figure skating and stripped of her 1994 U.S. championship, and ultimately pleaded guilty to hindering a prosecution, a felony. Her various exploits—an arrest, lady boxing, selling a sex tape—turned her into a punchline, but time—with a big assist from I, Tonya, in which she was played by Margot Robbie—helped turn her back into a human being (akin to how O.J. Simpson prosecutor Marcia Clark‘s legacy was reconsidered when Sarah Paulson helped re-humanize her in The People v. O.J. Simpson).

She even finished third on Dancing With the Stars in the spring of 2018.

Celebrating her 50th birthday on Sunday, Kerrigan can’t help being a part of pop culture infamy, one of countless celebrities who set out to be known for one thing but lost control of that narrative in the blink of an eye, through no fault of their own.

Nowadays she’s mainly a busy mom of two sons and a daughter (as well as honorary kid Phoebe, the family’s German shepherd), but she remains in demand on the public speaking circuit, talking about her own struggles as well as advocating for women’s empowerment.

“I really don’t look back unless someone asks me to look back, and then I have to,” she told USA Today in 2014 when the paper revisited the attack 20 years later. “Otherwise, why would I? I was attacked.”

David Madison/Getty Images

But when she executive produced Why Don’t You Lose 5 Pounds?, a documentary telling the stories of athletes battling eating disorders, she knew what awaited her while doing press for a project she cared about it.

Asked what it was like to watch herself in the aftermath of the attack, footage saved for posterity on YouTube, she told ABC News in 2017, “It’s sad, it’s almost like somebody else at this point.”

People can say what they want about why she got famous, Kerrigan concluded. “Because I have two Olympic medals,” she said. “They didn’t just give them to me. I mean, I worked hard for it.”